My Musical Identity

Ariana as Hinearoaropari in Onepū. Photographer: Julie Zhu, courtesy of Atamira Dance Company.

Hineraukatauri loves being on her own. She has no FOMO. She has something more like FOLHO (Fear of Leaving Home). She loves her cocoon so much – represented in the pūtōrino – that she never leaves it. Her cocoon is the original tiny house and from here she attracts her lovers, and produces her offspring. From here she sings her mystical, sometimes barely heard, enchanting songs. But to hear them you must lean in.

I was the youngest of seven growing up in suburban Christchurch in the 70s and early 80s. We didn’t have Māori-strummed singalong parties, nor did I have oriori sung to me while floating in the waikahu of my mother’s womb. My Mum was from a working class Pākehā family in Central Christchurch, of English and Italian descent. A daughter of merchants and hoteliers. She used to save her pocket money to go on holiday in Sumner. Now only a 15-minute drive from the CBD. My Dad grew up at Rāpaki, on the Lyttelton Harbour, and his Mum came from Ōnuku, on the Akaroa Harbour.

Ariana (the baby) with her whānau

Although I’ve never lived at either of those kāika, I still feel most at home in Harbour towns. I loved hearing Dad’s stories about growing up at the pā. The battles they had with the Pākehā kids the next bay over. These stories linked me to my tīpuna. However back then, they were like patupaiarehe in the mist, slightly out of reach. I remember sending made-up plaintive songs to my ancestors in my night-time prayers, asking God to pass them on.

When I was little, I took myself off t Sunday School, in the Library of Rowley Primary School. Nobody else in my family went to Church, but a big part of the attraction for me was the singing. I wasn’t so shy at home, and remember hopping up on a chair in the lounge holding the mic attached to our new stereo, singing my favourite Sunday School song:

“Father Abraham, had many sons, many sons had Father Abraham, I am one of them, and so are you, so let’s just praise the Lord...”

I was 6 years old. The song had actions, and I wiggled various parts of the body but not too much in case I fell off my chair-stage. It was met by sniggers. My brothers called me “Goodie two-shoes”. Around that time, my oldest brother had just been to Aussie for a holiday. He brought me back a bright yellow sparkly-dressed ‘Superstar Barbie’ complete with her own microphone and a star-shaped stand.

My teachers would always write that I was “quiet” or “shy” in my school reports. It irritated me. It would send me into an internal rage. In primary and high school I performed in variety shows, choirs, orchestras and kapa haka. I learnt piano for a while, but never thought of following in Superstar Barbie’s stiff tippy-toed footsteps!

I majored in Māori Studies at university and joined the kapa haka group. It was led by Godfrey Pohatu, also the head of the Māori department, and his wife Toroa. Godfrey was a talented composer who wrote beautiful waiata. One of my favourites had the lyrics, “aue, taku Māoritanga, ko taku puna aroha, hei whakaora i ahau.” My Māori identity is a spring of aroha that revives me. Having grown up in Christchurch as a ‘half-caste,’ I was literally cast as an in-between. Kapa haka did a lot to help solidify my identity as Māori.

During this time, I learnt about the history of colonisation. It was devastating. I remember thinking, why didn’t the rest of the world stop the atrocities that occurred here? But looking back now, that was naive. There are abuses of power that are still happening today. I could ask myself the same question. Why aren’t people stopping it? Why aren’t I stopping it?

As a third-year student, I did a paper that Toroa taught about Māori writers and writing and we studied the work of songwriters such as Tuini Ngawai. Wartime classics by Tuini are still sung today, such as ‘E te Hokowhitu a Tu’, to the tune of Glenn Miller’s ‘In the Mood’. As part of this paper, there was a creative writing component, and I wrote some poems and waiata, two of which I still sing. ‘E Hoa’, a love chant, and ‘I Kā Rā o Mua’. The latter is a nostalgic, bluesy acapella song in English about the effects of colonisation. “I kā rā o mua, I would know my place, in my tīpuna’s time, I would know my face, things would not be easy, but they would be clear, we’d change as season’s change, we had our atua to steer...”

Cover image for Clothesline Conversation

I had a job at the Language Lab, where (in the pre-digital era) students would go to practice their language skills, listening and speaking into tape machines. When it was quiet, I listened to some of the records in their music collection. There were two that stood out. Mahinaarangi Tocker with her kōkako-clear voice singing political folk songs about Māori women in her Clothesline Conversation album, and Aotearoa’s album – of kaupapa Māori music, mixed with taonga puoro. I was intrigued. I didn’t even know there was such a thing as traditional Māori instruments.

The purple-wearing ensemble performing at the University of Canterbury Women’s Festival. From left: Cathy Sweet, Jacquie Hanham, Margreet Stronks, and Ariana (then known as Liane)

When I moved back to Christchurch at the end of 1991, I became involved with organising a Women’s Festival at Canterbury University. As part of the festival, I performed some of my songs with three other female singers at a lunchtime concert. We donned purple and sang earnest feminist songs, along with ‘Breaths’ by Sweet Honey and the Rock, and ‘Young Māori Woman,’ a song written by Hinepounamu (Bernice Martin) that was recorded on ‘Clothesline Conversations’.

“Every day we face the system that rejects your right to be, and you are one of many, who are longing to be free, but freedom is hard, for young Māori woman hands, and you dream about your freedom, and it’s dope and empty beer cans...”.

The following year I spotted a note on the board of the Women’s Room and met Leigh Taiwhati, who was looking for some other women songwriters to form a band. I was about to meet up with her when I bumped into Jacquie Hanham, one of the singers from the Women’s Festival, purple-wearing, nameless ensemble. The three of us formed the band Pounamu. Our first gig at a Woman-only dance was awful! The crowd was rowdy, and our acoustic sound did not rock their world. Luckily our début at the Christchurch Folk Club was more successful, packed with whānau, friends, and fellow students. Leigh left after one year, but we carried on performing regular gigs at the Christchurch Arts Centre, festivals, and tours for a few years after that. Te reo Māori was an important component of my waiata, and I would generally sing in te mita o Kāi Tahu. It was a political decision. Even though I wasn’t fluent, I wanted to express myself in my reo as much as possible. The waiata seemed to choose which language they wanted to come out in, and often they were bilingual. There wasn’t much contemporary music being performed in te reo at the time in Christchurch. As I learnt more reo, I incorporated it more into my songwriting. Although some of our kaupapa may have been confronting at that time for some, most people seemed to embrace our music, which covered issues such as poverty, domestic abuse, and institutional racism. Outside of kapa haka and school productions it was my first real experience of performing, so I felt a mix of imposter syndrome and anxiety over putting myself up on a stage and singing my own songs in front of people. But my songwriting and confidence as a performer developed.

Cover of Mihi album by Pounamu.

We were chosen by the Tahu FM iwi radio station to represent Te Wai Pounamu at TVNZ’s Gig on the Roof, which was televised on mainstream TV, performing with other kaupapa Māori groups of the mid 90s. Also, after performing at an environmental rally, we were chosen to be the New Zealand representatives on a young Pacific peoples delegation to Europe in 1995 to protest against the French nuclear testing in the Pacific, sponsored by the Body Shop.

My waiata were often about cultural identity, mana wahine, and Māori spirituality. Then there was also political kaupapa, such as the reggae song ‘Dole Bludger’ about the judgement of young people by society, “dole bludger, a real loser, is that what you think I am? Well will you ever go, to look beyond your nose and see me as a real woman?” and an urban cautionary tale, ‘Kia Tūpato’ – “remember what happened to Red Riding Hood, whilst picking those flowers she met up with no good. That nasty old wolf posing as her friend, but like all fairy tales, happy was her end. It ain’t like that, in our real world, ‘kia tūpato’ be careful girl...”.

By then I’d started working in libraries and museums, and in 1996 I moved to Palmerston North, to do a post-graduate diploma in Museum Studies. I became more interested in taonga puoro and ended up doing a practicum rehousing the taonga puoro collection at the Whanganui Museum. I also wrote about the taonga puoro revival, as a part of the decolonisation movement.

At the end of that year, I got together with my partner. We lived in Sydney and Auckland for a couple of years. Then in 1999, we moved back to Christchurch to be near my whānau, as I was about to give birth to my daughter Matahana. When she was still a baby, I attended a Hone Tuwhare poetry reading with her on my lap and she sat there, mesmerised. I asked Hone at the end of the session whether he needed isolation to write, and he said, “write what you know” and went on to say that as a new mother, I could write about that. I got home and immediately wrote a poem about not feeling guilty for the dishes not being done.

Around that time, I randomly met my old kapa haka teacher from school, in a supermarket car park and he asked what I was up to now. I replied, “oh, I’m just a mum at the moment”. He responded with “he mahi rangatira tēnā”. That got me thinking about the role of motherhood, and how it is absolutely fundamental, but isn’t valued enough. Looking back, these two experiences inspired me to write the ‘Whaea’ album. I realised I wanted to put something out into the world that celebrated motherhood.

Whaea album cover. Photo by Andrea Stagg

I’d had my son Tama-te-rā by this time also. We had home births and tried to incorporate Māori tikanga into the process. This included rongoā, and my tāne Ross recited an excerpt of an oriori when both babies were born. Later I wrote waiata about the power of breast milk, waiū, and one for burying our pēpi’s placenta, whenua ki te whenua. While researching, we found there weren’t many resources available about Māori birthing or parenting. I hoped that ‘Whaea’ might help others, who may not have access to this kind of knowledge in their whānau. I wanted to incorporate the sounds of taonga puoro on the album, so brought in Richard Nunns, who I’d met at a workshop not long before.

In 2003 we moved to Dunedin where I met a producer, Leyton, and we decided to do some recording at my big old draughty house in Sawyers Bay. He set up a vocal booth for me in the bathroom, which was carpeted and we recorded a chant that I’d written called Kōrakorako. It means an albino, pale-skinned person, or other-worldly being. It was written for both my son and my tāne Ross, the pale-skinned “tāne pūrotu” who I sing about in Kōrakorako. Ross never expects anyone to think he is Māori even though he has whakapapa to Ngāti Raukawa, Ngāti Toa and Kāi Tahu. The chant poses the questions: who am I, who are you? It’s about identity, and diversity within te ao Māori.

‘Kōrakorako’ was chosen to be part of a compilation of women’s music on the Loop label. On the back of this, Leyton and I got funding from CNZ to work on an album together. This became the ‘Tuia’ album, which moved my music into another direction. Most of the instrumentation is electronic, and taonga puoro played again by Richard Nunns. It was an interesting collaborative process, where I would come up with a vocal part, and then in the studio, we would build up layer upon layer of harmonies and counter-melodies. It was gruelling at times and I had to put a lot of trust in both Leyton and myself. He kept asking me if I had more in me. I don’t have much western musical training, so I rely upon gut instinct and courage. The song Matariki is made up of smaller chants, whispered parts, repeats of layered vocals, harmonies, and new lyrical ideas building up and up, then soars at the end with a karanga.

Louise Potiki Bryant created an ethereal video filmed at Rāpaki, with layered imagery, for the title track, Tuia. It won an indigenous film award in Canada. In the years since then I’ve been lucky to continue to collaborate with Louise. Most recently on her dance show ‘Onepū’ based on a southern story about elemental atua wahine. In this show which was based on a kōrero from my Pōua’s book ‘Tikao Talks’, I played Hinearoaropari, the atua of the echoes that resound off cliffs. I also created the music with Paddy Free, where I played a whole range of taonga puoro, and wrote waiata specifically for the show.

In the early 2000s, I met Brian Flintoff at his workshop in Nelson. He showed me how to get a sound out of a kōauau, by whistling into it first, and then subtly moving the instrument’s angle until the sound came from the split air bouncing off the inside chamber of the instrument. To my surprise it came quite easily and then – I was hooked. I had previously thought that you needed to be an expert to play them, a tohunga. But how can you become a tohunga at something without being a beginner first?

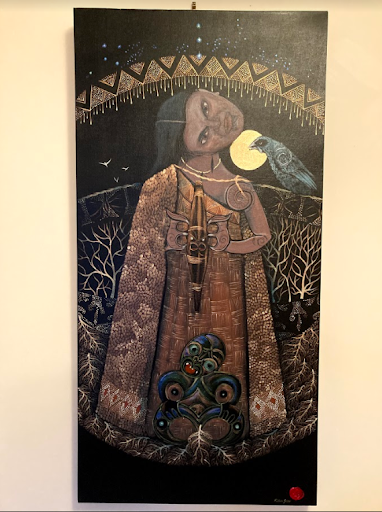

Te Waha o Wheke artwork by Robin Slow, which features Hineraukatauri and her daughter Wheke

Taonga puoro has now become a huge part of not only my musical identity, but my personal identity. I now live in Wellington, where there are many other taonga puoro geeks to play and collaborate with. One of our favourite things to do, is to go and play out in the environment in different locations around Wellington. Within my study of rongoā/healing, I’m also incorporating taonga puoro. This feels like a natural progression or homecoming for them as they come back to their original context.

Earlier on, I talked about my annoyance at being called ‘quiet’ in my school reports. Since then, I’ve realised that this introverted nature is a big part of who I am. I’ve developed tools to feel more comfortable about performing, mostly through karakia, and connecting spiritually with my tīpuna, and just to be tau, or settled in my own mana takata. As wāhine, we have a right to be up on that stage, or whatever platform it is. Or, we can just choose to play for our own purposes, whether for our wellbeing, or singing our pēpi to sleep.

I saw you in a dream, and then you became my reality. Sun-shining face, you’re full of grace. Peninsular.

I’m singing you to sleep, my heart, my soul in you I keep. Sun-shining face, you’re full of grace. Peninsular.